The first images from the Solar Ultraviolet Imager (SUVI) instrument aboard NOAA’s GOES-16 satellite captured a large coronal hole on the sun on January 29, 2017. The sun’s 11-year activity cycle is currently approaching solar minimum and during this time powerful solar flares become scarce and coronal holes become the primary space weather threat. Once operational, SUVI will capture full-disk solar images around-the-clock and will be able to see more of the environment around the sun than earlier NOAA geostationary satellites.

The sun’s upper atmosphere, or solar corona, consists of extremely hot plasma, an ionized gas. This plasma interacts with the sun’s powerful magnetic field, generating bright loops of material that can be heated to millions of degrees. Outside hot coronal loops, there are cool, dark regions called filaments which can erupt and become a key source of space weather when the sun is active. Other dark regions are called coronal holes, which occur where the sun’s magnetic field allows plasma to stream away from the sun at high speed, resulting in cooler areas. The effects linked to coronal holes are generally milder than those of coronal mass ejections, but when the outflow of solar particles is intense, they can still pose risks to Earth.

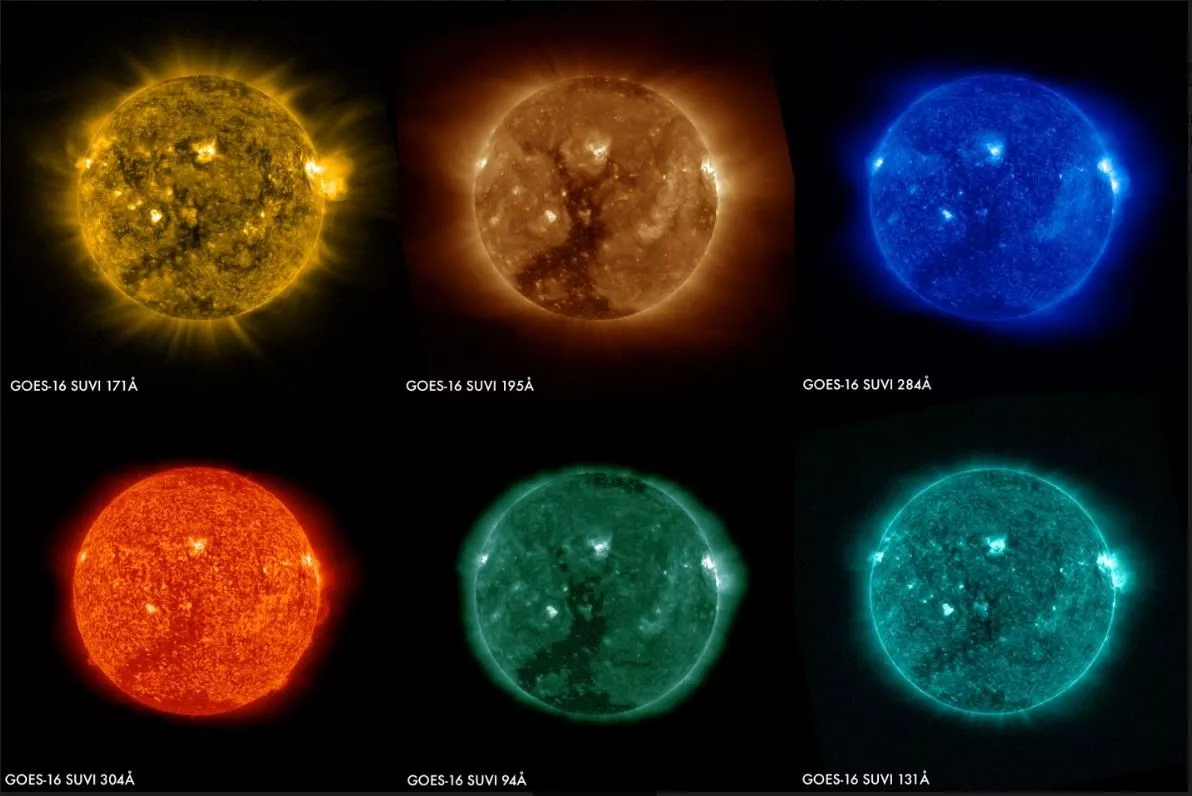

The solar corona is so hot that it is best observed with X-ray and extreme-ultraviolet (EUV) cameras. Various elements emit light at specific EUV and X-ray wavelengths depending on their temperature, so by observing in several different wavelengths, a picture of the complete temperature structure of the corona can be made. The GOES-16 SUVI observes the sun in six EUV channels.

Note: GOES-16 data are currently experimental and under-going testing and hence should not be used operationally. To see more imagery from GOES-16 and other updates about the satellite, visit the GOES-16 image gallery.